In this final article in our series of studies looking at Euro-2020-related infringements, we revisit domain name infringements and consider activity across other online channels, with a focus on social media and mobile apps.

Following the original study, which looked at domains registered before May 2020 with names containing 'euro2020' or 'euro2021'[1], we analysed daily activity levels in the period immediately preceding and during the competition. As with the previous research, CSC made use of information from domain registry zone files to identify any newly registered and de-registered / lapsed domains with names containing variants of the competition name.

During the monitoring period, we identified 203 new domain registrations, plus 25 pre-existing registrations that had lapsed. The daily numbers of new domains are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Daily numbers of registered domains with names containing 'euro2020' or 'euro2021' (or variants). The red dashed line shows the seven-day centred rolling average.

The analysis showed variable but continuing levels of activity throughout the period, but with average daily numbers of registrations somewhat higher prior to the competition than during it. This suggests that the registrants may have set up their sites early to maximise the length of time they could make use of them.

In terms of website content, many of the same types of sites identified in the first study continued to appear. At least 10% of the total of the newly-identified examples again included the promotion of betting or gambling services, together with others featuring content relating to match streaming, ticket sales, or competition or prediction websites.

However, among the websites hosted on the domains registered after May 21, we observed a new set of trends:

- Several sites (including some of those promoting gambling services) included references to cryptocurrency schemes (see Figure 2a). Such schemes are generally unregulated, and this type of site may be associated with fraudulent activity, raising the possibility for users to experience financial losses, theft of personal data, or exposure to malicious content.

- Domains with names featuring references to individual teams were increasingly identified. Particularly in the later stages of the competition, we observed a number of domains referencing England and Italy (or 'Italia') - the eventual finalists in the competition. Between July 1 and 11, we identified seven domain names including 'England' and two including 'Italy'. Six of these nine included the term 'winners' (registered pre-emptively). At the time of analysis, many of these sites resolved to low-relevance content (e.g. sites with pay-per-click links). They may have been registered as a means of generating click-through revenue, or to sell on the domains at an inflated price after the competition. However, some of the domains did resolve to content relevant to the team in question (see Figure 2b).

- A number of sites included log-in forms (see Figure 2c) or had been explicitly flagged as dangerous or fraudulent at a browser level. Some of these were already inactive by the time of analysis. Any such sites soliciting for personal details pose a potential risk if not legitimate or authorised.

Figure 2: Examples of site content identified on domains with names containing 'euro2020' or 'euro2021' and registered after May 21, 2021: (a) cryptocurrency-related content; (b) an e-commerce site selling England merchandise; (c) a branded site including a log-in form.

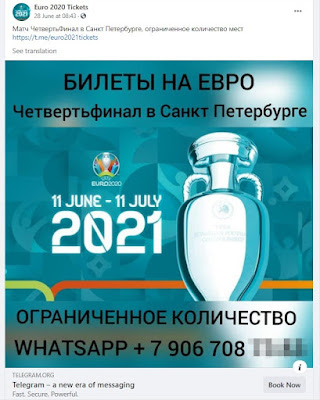

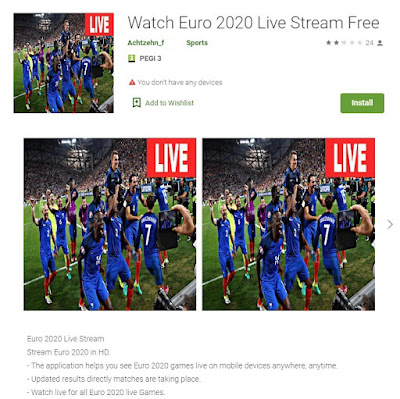

The threat landscape is not restricted just to standalone websites hosted on competition-specific domain names. We identified similar content on other channels, including social media and mobile apps. Figures 3 and 4 show examples of a range of content found in searches carried out in the final week of the competition. We also identified other types of potentially lower-threat content relating to Euro 2020 across the same channels, including:

- Large numbers of informational and fan pages on Facebook

- Profiles providing competition news and updates on Twitter

- Mobile apps comprising score update services, competition predictors, or games

(b)

(c)

Figure 3: Examples of content identified on social media profiles: (a) offering ticket sales; (b) promoting gambling services; (c) offering the sale of merchandise; (d) offering match streaming.

Figure 4: Examples of content identified in mobile apps: (a) a purportedly official app produced by a third-party developer; (b) an app offering match streaming.

While a subset of the findings in this study may be legitimate, much of the content we observed presents the potential for risk to customers and brand (trademark) owners, especially in cases where the material is not official or authorised. These include financial losses and reputation damage, and can be associated with phishing activity, the sale of counterfeit products, non-legitimate cryptocurrency schemes, fake gambling sites, distribution of malicious content, illegal distribution of copyrighted content, traffic misdirection, and the unauthorised use of brand terms or official imagery.

The range of online channels on which this content appears also highlights the importance of a holistic brand-protection service - encompassing both monitoring and enforcement - covering as many of these channels as possible. This is important not just because the different areas of the Internet comprise different ecosystems in which the same types of issues can manifest, but also because there is so much overlap between these areas. Familiar examples might include mobile apps linking to e-commerce marketplaces, or social media profiles promoting standalone websites.

Even within a single online channel, it is important for the coverage to be as comprehensive as possible. Where mobile apps are the area of interest, for example, a brand-protection programme should cover not just the main app stores like iTunes, Google Play, etc., but also the myriad standalone APK sites where app files are available for download. This latter category of site can actually be a source of greater concern, since the apps offered here generally undergo less quality control, and are more prone to be unofficial, out-of-date, or associated with malicious content. Similarly for e-commerce, it is important to consider not just the common, well-known marketplace sites, but also to include an element of discovery within the monitoring, to identify previously unknown, standalone sites.

For some programmes, or for monitoring associated with particular events, it may be prudent to cover the areas of the Internet beyond those accessible using the standard techniques of search-engine meta-searching, link crawling, domain zone file analysis, and direct site searching. Where phishing is a concern, CSC advises augmenting these services with a dedicated phishing monitoring programme. CSC’s services use a combination of spam traps, honeypots, and other data feeds to find content that may not be identifiable through other routes[2].

In the closing week of the Euro 2020 competition, a news story emerged in which an e-commerce site selling retro football shirts and merchandise was subject to a cyber attack where customer details were compromised. This led to a targeted e-mail phishing scam where recipients were offered a cashback bonus, to be claimed via a web form where they had to share their card details. The phishing e-mails used a typosquatted domain name - just one letter different from the official domain[3]. This case highlights not only how the types of targets for criminal activity can be influenced by external events, but also the importance of holistic monitoring. Domain monitoring and phishing detection can provide early warning of this type of scam.

The identified infringements associated with Euro 2020, as presented across our three articles[1,4], can have a number of victims. These include the owners of trademarks associated with the competition and teams, official partners and sponsors, and members of the public. They also highlight how a high-profile event can drive criminals to focus their attention towards content and channel types receiving - albeit temporarily - increased levels of attention and web traffic. However, the Euro 2020 name is just one ephemeral example among an almost limitless range of brand names and ongoing events. Overall, these findings highlight the importance of continuous monitoring and enforcement, using a programme approach that is flexible enough to change focus onto new areas of concern as they emerge and grow.

References

[1] https://www.cscdbs.com/blog/illustration-of-real-world-events-and-online/

[2] https://www.cscdbs.com/blog/phishing-scams-how-to-spot-them/

[3] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-57766908

[4] https://www.cscdbs.com/blog/ecommerce-marketplace-activity/

This article was first published on 27 July 2021 at:

https://www.cscdbs.com/blog/euro-2020-part-3-domains-revisited-and-other-channels/

Also published at:

https://circleid.com/posts/20210816-euro-2020-part-three-domains-revisited-and-other-channels