Introduction

A few weeks on from the launch of the .zip domain extension (an example of a 'top-level domain', or TLD), and just as the .box TLD is set to launch, we consider the cybersecurity and infringement risks presented by the new registrations.

.zip is one of the most recent in a long line of new TLDs launched since the start of the new-gTLD programme in 2012[1], entering its General Availability phase (in which domain registrations are open to all) on 10-May-2023[2].

The reason for concern with this particular extension is the potential for confusion with a digital file suffix commonly used for compressed or archive data files ('zip files') and the possibility that this confusion may be exploited by bad actors to drive Internet users to their own content, distribute malware, and/or create brand infringements.

These types of abuse can be manifested in a range of different ways:

- Many platforms and e-mail clients will automatically convert certain types of string into URLs, so a legitimate filename such as document.zip could be interpreted as a URL which, when clicked, may drive users to the corresponding domain name if registered[3,4]. Similarly, if a user searches for a non-existent zip-file name, file explorer applications may instead perform an online search directing the user to a corresponding .zip domain name.

- The DNS queries associated with a link-click can provide information to the site owner on the name of the file being requested, which could correspondingly result in a leakage of sensitive information[5]. This may be particularly effective if the second-level name ('SLD') of the registered domain (i.e. the part of the domain name before the dot) is a file extension (such as .doc) in its own right - e.g. a domain such as doc.zip might allow the site owner to see that a file such as sensitivedocumentname.doc.zip has been requested.

- The TLD presents the possibility for a link to a potentially malicious .zip domain to easily be disguised as a link to a zip file on a trusted website[6], or as content embedded in a malicious e-mail.

- Domains hosted on the .zip TLD may be more likely to be trusted by users based on their familiarity with regular zip files.

- Conversely, as the .zip extension becomes more well-known, users may unknowingly download a zip file - which can contain arbitrary content of unknown legitimacy - thinking that they are simply clicking on a link to a regular website[7].

Domains on the .zip extension are being offered by Google Domains[8], together with a number of others - including .mov, which launched on the same day, and is subject to similar security concerns due to the possibility of confusion with the video-file format suffix. Despite the claim that the domain extension is intended to represent content from providers who are "fast, efficient, and ready to move", the risks - combined with other Google offerings which are attractive to would-be attackers, such as a whois privacy service and subdomain forwarding - mean that the domains on this new TLD may warrant careful scrutiny.

In a similar vein, the .box domain extension is set to enter its Sunrise phase - where brand owners can apply for new domains, prior to General Availability - on 09-Aug-2023[9]. Whilst not a file suffix in the same way as .zip, the .box extension is also likely to be subject to abuse, in part due to the possible scope for confusion with content relating to the Dropbox hosting and file-sharing service. Other brand names incorporating the term 'box' (such as Xbox and Birchbox) may also find themselves particularly targeted by attacks, and we anticipate that this additional new TLD may also be worth closely watching once general registrations commence.

.zip registrations in the first two months of activity

The .zip extension has seen a rapid growth in the numbers of registrations in the weeks since its launch - in part, presumably, due to its attractiveness to bad actors. Within the first month, it was already the most popular of Google’s eight new registration offerings by a significant margin[10]. However, it is worth noting that some of the registered domains feature warnings of the potential for abuse, or have been registered so as to block use by bad actors.

In this article, we use DNS zone-file information to conduct a comprehensive study of registered domains across the TLD, to analyse potential indicators of intention for nefarious use. This work follows on from previous studies, which already found five active phishing sites - targeting the Microsoft, Google, and Okta brands - within a week of launch of the TLD[11] and numerous other domains featuring keywords (such as 'install' or 'update', other brand-related terms, or long, non-sensical strings) of concern, due to the potential of their association with filenames or downloadable tools, and/or the corresponding phishing and malware risks.

As of 21-Jul-2023, there were 29,664 distinct .zip domains registered. 266 of these comprised just a string which is also used as a filename suffix[12] as the SLD, with the following common examples all found to have been registered: apk, css, doc, docx, exe, htm, html, gz, jpeg, jpg, mov, mp3, mp4, php, ppt, pptx, rar, sql, tar, tmp, wav, xls, xlsx, xml, and zip itself (as apk.zip, css.zip, etc.).

The following statistics illustrate the numbers of domains with SLDs featuring keywords of particular interest or concern:

- 359 domains feature the term 'file', 280 'update', 170 'install', 112 'download', and 53 'invoice'.

- The top four most valuable global brands in 2023[13] are all technology brands, and therefore compelling candidates for infringements using the .zip extension. Of these, 'apple' features in 12 domains, 'google' in 49, 'microsoft' in 49, and 'amazon' in 7. Other related product names also feature in the dataset, with 82 'windows' domains and 31 'chrome'.

Overall, this yields a dataset of 1,093 domains (3.7% of the total) containing one or more of the above high-risk keywords. Of these, 415 (38.0%) return an HTTP status code of 200 (i.e. some sort of live website response). Some of these provide a relatively light-hearted proof-of-concept illustration of the risk of misdirection, with twenty-three (including archivedfile[.]zip, chrome-browser[.]zip, emergencyupdate[.]zip, and important-files[.]zip) re-directing to videos of Rick Astley's 'Never Gonna Give You Up' - the Internet practice known as 'Rickrolling'[14] - although a number of more concerning examples were identified, such as those outlined below, each of which has the potential to be distributing malicious content:

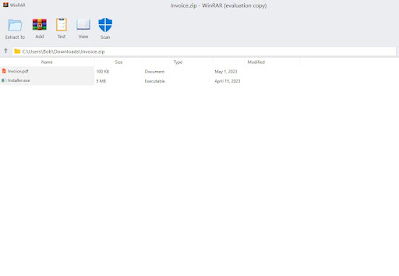

- Figure 1(i): Microsoft-related domain name resolving to a website displaying a 'file explorer'-style page referencing downloadable files

- Figure 1(ii): Website which automatically downloads an archive file named quarterly_figures_q2_2023.invoicestuff.zip

- Figure 1(ii): Website purportedly offering the download of a number of software applications

(i)

(ii)

(iii)

Figure 1: Examples of live websites with content of potential concern hosted on .zip domain names

Altogether, 38 of the domains in the dataset of 1,093 high-risk domains included the keyword 'login' at some location within their HTML (site content), indicating possible use for phishing activity.

Other examples of domains re-directing to apparently-unrelated third-party sites were also identified - these may be taking advantage of misdirection tactics, even if not explicitly malicious.

However, very few of the domains appear to have been registered by official brand owners for legitimate use or to protect customers, with just four re-directing to URLs on the microsoft.com site, two on google.com, one on office.com, one on ubuntu.com, one on malwarebytes.com, one on archive.org, and one on square-enix.com.

Another key observation is the fact that the dataset of all .zip domains contains disproportionately many names consisting of long, apparently non-sensical strings of characters, compared with the general domain population. These types of domains have been noted previously as commonly being associated with phishing activity, through such tactics as the construction of deceptive URLs. The observation can be shown quantitatively by calculating the distribution of domain-name entropy values ('Shannon entropy', a method of quantifying the amount of randomness, or unpredictability, of a SLD string) within the .zip dataset, compared with the distribution amongst a set of all domain name registrations from a particular day, from a previous study[15] (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of domain-name entropy values for the dataset of .zip domains (red), compared with a set of general domains from a previous study (blue)

This analysis shows that the .zip domain distribution is significantly more weighted towards the high-entropy end of the spectrum (with a second peak at values above 4, and an average entropy value across the whole dataset of 3.39), compared with the domains from the general dataset (average entropy = 2.86).

Within the set of .zip domains, virtually all of the domains with entropy values about 3.85 (14,659 domains, or 49.4% of the total) consist visually of apparently-random strings (see Table 1).

| Domain name |

Entropy value |

|---|---|

| g0kfctpdb18t7vkidqj2me5ls9rjo46g.zip | 4.6875 |

| r5s0mo4tl315achnpvrkie76j84unba2.zip | 4.6875 |

| abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxy.zip | 4.6439 |

| 98lgdq7c064nmbs1olvuejsnvhbt82ri.zip | 4.6250 |

| cph1ukfm2n1bvd8jsaqetc3o47a7lfq6.zip | 4.6250 |

| cr9qpcoiaklt1f53m6bj0u07r3eud2k4.zip | 4.6250 |

| g4umroti85bj0vfes01d3oqau2n74fpj.zip | 4.6250 |

| hj23qhtvgcsd4pqcs765r8meuf014dba.zip | 4.6250 |

| ke6h76jnpefh2s2aivau98mc453ogtb7.zip | 4.6250 |

| l5eujm8vksnetqd1714fm2o3a3hgrpkd.zip | 4.6250 |

| mlf7v0nmbhia9rgil68jsp15qk2s0ech.zip | 4.6250 |

| piuvk9qg4indoljemab245fks3cn075b.zip | 4.6250 |

| 1cd7as0m8kpv1l0j5tnfqih2ot5tqge3.zip | 4.6014 |

| 3uav01gor6482mj2t6k9bp50ofkl7qio.zip | 4.6014 |

| 9q7f61obtugmpn8tj0i3r1bcmahsk5ft.zip | 4.6014 |

| apnv6golm5r3kp4f3jst744qbuh218n6.zip | 4.6014 |

| lms1acrubko51qqht7lf94138v0i0ndh.zip | 4.6014 |

| obdpfj3t963u7rltac095lmp1hi3g82q.zip | 4.6014 |

| so5eip1av0krpe3pthq7dnngd3bumfcl.zip | 4.6014 |

| to7liok38ijgud5hchs0rvmtiab9e2fe.zip | 4.6014 |

Table 1: Top 20 .zip domains by entropy values

None of the above domains was found to resolve to any live content as of the time of analysis (24-Jul-2023).

Conclusions

By the nature of its potential confusion with a filename suffix, the .zip TLD presents significant risk for both brand owners and Internet users, in terms of the possibility for brand infringements and potential association with phishing activity and malware distribution - and the risk for brand damage which this entails. Already, the registration patterns across this domain extension are indicative that the TLD is likely to be popular with bad actors, by virtue of the keywords and domain-name structures observed in the current dataset, together with the presence of live content of concern in some cases. We also anticipate that the .box domain extension, set to see its initial launch on 09-Aug, may also transpire to be subject to similar types of abuse.

These observations highlight the importance of brand owners taking a proactive approach to monitoring and enforcement with domains, allowing timely detection of - and action against - threatening registrations, through a programme of brand protection which is able to tackle new TLDs as soon as they launch, and identify new domain registrations on a daily basis.

References

[1] https://newgtlds.icann.org/en/program-status/delegated-strings

[2] https://tld-list.com/launch-schedule

[5] https://blog.talosintelligence.com/zip-tld-information-leak/

[6] https://medium.com/@bobbyrsec/the-dangers-of-googles-zip-tld-5e1e675e59a5

[7] https://www.iptwins.com/en/2023/05/25/domain-names-in-zip-beware-of-security-threats/

[8] https://domains.google/tld/zip/

[9] https://newgtlds.icann.org/en/program-status/sunrise-claims-periods

[10] https://blog.talosintelligence.com/zip-tld-information-leak/

[11] https://www.netcraft.com/blog/phishing-attacks-already-using-the-zip-tld/

[12] https://gist.github.com/securifera/e7eed730cbe1ce43d0c29d7cd2d582f4

[13] https://www.kantar.com/inspiration/brands/revealed-the-worlds-most-valuable-brands-of-2023

[14] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rickrolling

[15] https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/investigating-use-domain-name-entropy-clustering-results-barnett/

This article was first published on 22 August 2023 at:

https://www.iamstobbs.com/opinion/un-.zip-ping-and-un-.box-ing-the-risks-associated-with-new-tlds