Introduction

The final quarter of each year marks greater levels of shopping activity, with increasingly significant proportions of the worldwide spend taking place through online sales channels. Aside from the run-up to the period of Christmas and other end-of-year holidays, a number of other events are becoming more extensively adopted for sales promotions. These include the (predominantly Chinese) Singles Day on November 11 ('11-11'), and the weekend following the US's Thanksgiving holiday (generally referenced as 'Black Friday' and 'Cyber Monday').

It has been noted previously[1,2] that one manifestation of this activity on the Internet is the registration of large numbers of domains geared towards e-commerce, which can be of particular concern to brand owners when these domains are making use of trusted brand names to drive traffic to the sites, or are selling counterfeit or otherwise infringing products.

In this article, we look at the set of registered gTLD (generic extensions, such as .com, etc.) domains with names containing either 'black(-)friday' or 'cyber(-)monday' (with optional hyphens in both cases), as of the start of the lead-up to the holiday period (at the end of September 2023)[3].

Analysis

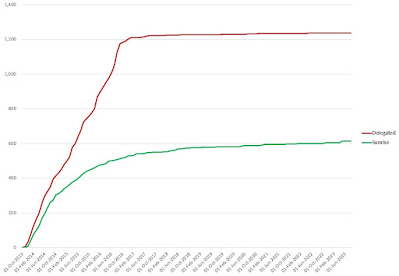

At the end of Q3 2023, there were a total of 6,596 registered gTLD domains with names containing 'black(-)friday' or 'cyber(-)monday' (hereafter referred to as 'Black Friday domains'). Considering those domains for which creation dates were available via automated whois look-ups, there is a striking annual cycle apparent in the registration activity (Figure 1). Whilst the general visible upward trend year-on-year is not necessarily indicative in itself of an overall increase in registration activity over time (since many of the domains registered in previous years will have expired prior to the date of analysis), it is very clear that there are spikes in activity in the fourth quarter of each year, representing domains registered to be utilised over the Black Friday period.

Figure 1: Numbers of Black Friday domains in the dataset by month of registration (Jan 2000 - Sep 2023)

Within the set of domains, a number of other trends are immediately apparent. Perhaps unsurprisingly, significant numbers of the domains contain additional keywords (within the second-level domain name (SLD), or portion of the domain name to the left of the dot) indicating that their primary function is e-commerce (Table 1).

Keyword

|

No. domains

|

| auction |

6 |

| buy |

38 |

| code |

15 |

| coupon |

30 |

| deal |

905 |

| discount |

54 |

| flash |

17 |

| market |

14 |

| offer |

81 |

| promo |

21 |

| sale |

448 |

| saving |

21 |

| shop |

102 |

| store |

54 |

| voucher |

1 |

Table 1: Numbers of Black Friday domains featuring e-commerce keywords in their SLD

Additionally, several are dedicated to specific product types (Table 2).

Keyword

|

No. domains

|

| accessor* |

1 |

| air(-)fryer |

2 |

| appliance |

6 |

| camera |

8 |

| cellphone |

17 |

| electronic |

25 |

| gaming |

17 |

| laptop |

47 |

| smartphone |

9 |

| vacuum |

10 |

* for 'accessory' or 'accessories'

Table 2: Numbers of Black Friday domains featuring product-specific keywords in their SLD

Perhaps even more directly concerning, from a brand-protection point of view, are any domains with names containing brand names. Table 3 shows the number of domains with SLDs containing the names of each of the top ten most valuable global brands in 2023[4].

Keyword

|

No. domains

|

| apple |

5 |

| google |

0 |

| microsoft |

0 |

| amazon |

12 |

| mcdonalds |

0 |

| visa |

0 |

| tencent |

0 |

| vuitton |

3 |

| mastercard |

0 |

| coca(-)cola |

0 |

Table 3: Numbers of Black Friday domains featuring the names of any of the top ten most valuable brands in their SLD (excluding obviously official domains)

Interestingly, of the brands on this list, only Apple, Amazon and Vuitton (makers of technology or luxury brands, or customer-facing brands directly related to e-commerce) are represented in the dataset. However, there were a number of additional brands for which significant numbers of domains were identified (Table 4).

Keyword

|

No. domains

|

| walmart |

14 |

| a(-)prime* |

14 |

| moncler |

3 |

| lv(-)bag** |

3 |

| ugg(-)boot |

3 |

| beats*** |

2 |

| gucci |

2 |

* presumably in reference to Amazon Prime

** presumably in reference to Louis Vuitton

*** of which 1 references 'bydre' explicitly

Table 4: Numbers of Black Friday domains featuring other brand terms in their SLD (excluding obviously official domains)

As of the time of analysis, none of these branded domains currently resolved to any active e-commerce site, although (given the timeframe) it is possible that they have simply been registered well in advance of the holiday season, with the intention of subsequently having their intended content uploaded. In these types of instance, brand owners would be advised to monitor the sites to track for content changes, with the option of launching a takedown action when infringing content appears. In some cases, the domains were found to resolve to gambling-related and/or adult content, potentially as a means of monetising the domain name in advance of its future use (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Examples of gambling sites hosted on brand-specific Black Friday domain names (SLDs: 'louisvuitton-blackfriday' and 'beatsbydrecybermonday', respectively)

Amongst the remainder, several others were found to comprise instances of misdirection (e.g. domains resolving to sites pertaining to affiliate schemes), sites monetised using pay-per-click links, pages offering the sites for sale, and other instances displaying messages that the sites have already been suspended.

A number of other themes were also apparent within the wider dataset, including several domains featuring Web3-related keywords - 'coin' (27, of which 23 reference 'bitcoin' explicitly), 'crypto' (5 domains), 'token' (2) and 'nft' (2). It is also noteworthy that domain names of the form blackfridayXXXX.com and cybermondayYYYY.com have been registered for every value of XXXX between 2009 and 2040 and between 2051 and 2070, and for every value of YYYY between 2009 and 2052.

Considering other aspects of the full dataset (in this case, excluding 517 domains which appear likely to be under the legitimate control of brand owners, on the basis of their registration via enterprise-class registrars of the type often used by these entities - i.e. looking at the remaining 'potentially unofficial' domains), the top TLDs represented are shown in Table 5.

TLD

|

No. domains

|

| com |

4,324 |

| site |

331 |

| net |

256 |

| live |

132 |

| org |

130 |

| online |

87 |

| info |

75 |

| shop |

69 |

| space |

43 |

| xyz |

39 |

Table 5: Top TLDs represented in the dataset of (potentially unofficial) Black Friday domains

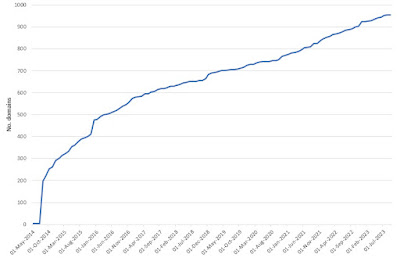

Perhaps more informative is to consider these numbers as compared with the total number of domains registered across the TLDs in question, to see if certain TLDs are disproportionately more utilised by the domain registrants. This analysis is shown in Figure 3, where the solid line shows the expected numbers of Black Friday registrations, as a function of the total number of domains on each TLD, if all TLDs were utilised equally, and using the numbers for .com as a benchmark. Any TLDs which appear above this line (such as .site and .live) therefore appear disproportionately more frequently in the dataset than might be expected.

Figure 3: Total numbers of (potentially unofficial) Black Friday domains by TLD, as a function of the total number of registered domains on that TLD

The data can equivalently be presented by consering the frequency of Black Friday domains per million domains on the TLD in question. The most popular TLDs in the dataset are shown in Table 6 (excluding any TLDs for which fewer than 5 Black Friday domains were present).

TLD

(and N, no. of Black Friday domains)

|

Frequency of Black Friday domains

(per million domains on TLD)

|

| deals (26) |

2762.70 |

| sale (38) |

2633.59 |

| bargains (5) |

2507.52 |

| codes (16) |

895.26 |

| fyi (35) |

556.07 |

| zone (24) |

540.48 |

| shopping (5) |

431.63 |

| site (331) |

236.43 |

| live (132) |

209.56 |

| space (43) |

109.86 |

Table 6: Top TLDs by frequency of (potentially unofficial) Black Friday domains (where N ≥ 5)

It is striking (though perhaps not surprising) that five of the top ten TLDs are explicitly related to e-commerce. More generally, new-gTLDs (such as .xyz and .top) - which have been noted previously as being disproportionately utilised for fraudulent registrations[5,6,7] - are extensively represented within the dataset.

The mix of registrars represented in the dataset (Table 7) is also noteworthy. The list is dominated by retail-grade providers, many of which are popular with infringers due to typically low compliance to enforcement requests.

Registrar

|

No. domains

|

| GoDaddy.com, LLC |

1,935 |

| NameCheap Inc. |

483 |

| Gname.com Pte. Ltd. |

211 |

| Key-Systems GmbH |

201 |

| PDR Ltd. d/b/a PublicDomainRegistry.com |

197 |

| Squarespace Domains II LLC |

177 |

| NameSilo, LLC |

148 |

| Dynadot Inc |

107 |

| Tucows, Inc. |

95 |

Table 7: Top registrars represented in the dataset of (potentially unofficial) Black Friday domains

Indeed, within the full dataset, over 2,000 of the domains were found to resolve to some sort of live website content and, of these, a number of examples were identified of sites featuring explicitly infringing or otherwise illegal content (e.g. the sale of counterfeits) (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Examples of Black Friday domains resolving to live, apparently infringing or illegal content (SLDs: 'raybansblackfriday', 'reebokblackfridayoffers', 'salomonblackfridaysales', 'montecwearblackfriday', 'tevasaleblackfriday', 'blackfridayssaving')

Conclusions

As with other high-profile events, the start of the 2023 holiday shopping season shows signs of a increasing number of domain registrations relating to Black Friday and Cyber Monday and - assuming trends are similar to those seen in previous years - we can only expect the numbers to grow over the coming weeks.

It is clear that many of these domains are intended for infringing use - not least because of the significant numbers of sites already found to be resolving to egregious content - highlighting the importance of brand owners conducting a rigorous programme of monitoring and enforcement, especially over key periods when levels of activity are typically high. The statistics also show that significant numbers of domains are typically registered well in advance of the season itself, itself showing the advisability of tracking new registrations for subsequent changes in content.

Of course, domains are always only part of the picture. In today's increasingly connected Internet, e-commerce can take place across a wide range of online channels, including marketplaces, social media, mobile apps, and the wide range of other general Internet content (including standalone websites hosted on non-brand-specific domain names). Accordingly, a holistic approach to brand protection, addressing the full range of relevant areas, is of key relevance.

References

[1] https://www.cscdigitalbrand.services/blog/how-will-black-friday-ecommerce-domains-trend/

[2] https://www.cscdigitalbrand.services/blog/holiday-shopping-events-part-2/

[3] The analysis is carried out using data from the zone files available from ICANN's Centralized Zone Data Service (https://czds.icann.org/home), covering gTLDs and new-gTLDs. All information is as per the zone files downloaded on 28-Sep-2023, which were available for 1,082 TLDs (extensions).

[4] https://www.kantar.com/inspiration/brands/revealed-the-worlds-most-valuable-brands-of-2023

[5] https://circleid.com/posts/20230117-the-highest-threat-tlds-part-2

[6] https://www.iamstobbs.com/opinion/the-randomest-domain-names-entropy-as-an-indicator-of-tld-threat-level

[7] https://www.iamstobbs.com/opinion/the-new-new-gtlds

This article was first published on 6 October 2023 at:

https://www.iamstobbs.com/opinion/web-dot-coms-but-once-a-year-holiday-shopping-activity-part-1-black-friday-domains