BLOG POST

The online prominence of brands can be a key metric for brand owners, and can serve as a data input for a number of areas, including search-engine optimisation (SEO) and web-traffic analysis, and brand valuation. Overall, it provides a measure of the amount of accessible brand-related online content - both official and third-party - and can also provide an indication of the likelihood of a brand being targeted by infringers.

We have developed a simple methodology for quantifying the relative online prominence of brands, based on the concept of 'brand content score' (a metric for measuring the amount of brand-related content on an individual webpage), using a sample of the most highly-ranked search-engine webpages returned in response to relevant search terms. We have applied this principle to the top twenty fashion brands of 2023.

The analysis finds that the top five most prominent fashion brands are Nike, Gucci, Skims, Dior, and Burberry. Significantly, no strong correlation was found between online prominence and brand rankings (as measured by the Lyst Index), though this is perhaps unsurprising given that Lyst attempts to reflect the frequency of use of brand-specific searches by Internet users, and mentions and engagement on other platforms such as social media. By contrast, our measure of prominence is focused specifically on search-engine visibility, and the extent of brand-related content on the most highly-related webpages (i.e. factors more closely connected with SEO).

However, the methodology does provide meaningful insights in its own right, and extensions to the technique could be applied to produce deeper-dives of content relating to specific industry areas, and allow analysis of other characteristics, such as brand sentiment.

This article was first published on 28 November 2023 at:

* * * * *

WHITE PAPER

Measuring online brand prominence: a proof-of-concept for the top twenty fashion brands

Introduction

The online prominence of brands can be a key metric for brand owners, and can serve as a data input for a number of areas, including search-engine optimisation and web-traffic analysis, and brand valuation. Overall, it provides a measure of the amount of accessible brand-related online content - both official and third-party - and can also provide an indication of the likelihood of a brand being targeted by infringers.

In this study, we present an overview of a simple methodology for quantifying the relative online prominence of a selection of brands, using the top twenty fashion brands in 2023 (Appendix A) as a case study.

Methodology

The basic principle behind the methodology is to obtain a representative sample of webpages of potential relevance (e.g. to the business area of the brands concerned) and then determine the number and prominence of mentions of each of the brands of interest on each webpage, across the dataset.

One of the main points to note in this type of analysis is that it is necessary not to explicitly search for any of the brand names in question. The reason for this is that - by definition - for any given query submitted to a search engine, all of the results will relate to the search term being used. Even if the analysis considers all such results, by continuing to paginate through until no further results are returned, this will usually only return a maximum number of results (typically a few hundred) for any given search engine and query. If, therefore, we simply search for each brand name separately, this will yield a relatively consistent number of results for each brand, and the brands will artificially appear to have similar online prominences. Instead, it is preferable to use generic search queries to bring back sets of pages relevant to the industry area of the brands in question (or to business in general) and count the mentions of the brands (and measure their prominence in each case) which happen to appear in this overall representative sample of pages.

In this analysis, we consider six generic fashion-related search terms ('fashion', 'fashion brands', 'clothes', 'clothing', 'designer' and 'trends'), and analyse only the first page of results (approx. 100) from google.com in each case. The list of results is then de-duplicated (to account for the fact that some pages are returned by more than one of these queries), yielding a dataset of 545 webpages of high relevance to fashion brands, for the proof-of-concept analysis.

The next stage is, for each of the twenty brands under consideration, to measure the number and prominence of the mentions of the brand on each of the pages in the dataset. In general, prominence is determined by the type of context in which the brand is mentioned (e.g. in the URL vs. the page title vs. a level-1 or level-2 heading vs. any other mention on the page); this analysis is carried out by considering the full content of the HTML source-code of the webpage.

In earlier formulations of similar methodologies[1,2,3], the analysis was carried out simply by considering the numbers of pages on which there was at least one brand mention in each of the key areas of content (URL, title, etc,) on the page. However, this approach is somewhat unsatisfactory, as it fails to distinguish (for example) a page which mentions a brand once in its page title from one featuring multiple mentions in the title (and, correspondingly, actually has a greater degree of 'brand-related' content). In this study, we present an improved methodology, utilising the concept of a 'brand content score' for each brand on each page.

Brand content score

The brand content score (which can be calculated for a specific brand or keyword on any given webpage) is a useful metric in its own right, with general applications in a range of areas. Its calculation involves counting each mention of the brand on the page, and weighting each one according to its prominence - e.g. a mention in the URL 'scores' more highly than a mention in the page title, which scores more highly than a mention in a level-1 heading, and so on. In our formulation, we also have the option to 'cap' the contribution to the total score from each specific area, to avoid skewing the results by 'junk' pages which may be 'stuffed' with very large numbers of mentions of random terms.

The range of scores obtained by this analysis will be dependent on the relative weightings and data caps used, as well as the types of search queries used to generate the results and the keywords being matched.

In brand monitoring, brand content score can also be used as a basis for prioritising results - for example, when large numbers of webpages are identified using a monitoring tool. Those pages assigned the highest scores - i.e. those of greatest potential relevance to the brand in question - are typically the primary targets for further analysis, may be priorities for further monitoring (e.g. content tracking) and enforcement, and can provide insight into keywords and TLDs (domain extensions) most used in relevant content, which can help inform domain registration policies[4,5].

In this analysis, we calculate the brand content score for each brand under consideration, for each webpage in the dataset, and use the mean value across all pages for each brand as the basis for the comparison of the relative online prominence of the 100 brands.

Findings

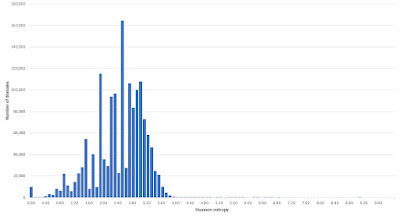

The distribution of the full set of brand content scores, for all brands across all webpages in the dataset, is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Distribution of all (non-zero) brand content scores, for all twenty brands and all webpages in the dataset

The vast majority of calculated scores across the dataset are relatively low (with a score of 10 or less calculated in 99.7% of cases), which is perhaps unsurprising in view of the fact that the set of pages is - by design - dominated by content about fashion generally, rather than comprising webpages about any of the relevant brands specifically. The highest score observed in the dataset was 76 (one instance), the brand content score calculated for the Skims brand, for a page on the official Skims website[6]. This was the only identified incidence in the dataset of a page from the official website of one of the brands under consideration being returned in response to one of the generic, fashion-related search queries used (returned as result #23 on google.com in response to the query-term 'clothing', and as #99 for 'clothes').

Overall, the relative online prominence of each of the top twenty fashion brands is expressed as the mean of the individual brand content scores for that brand, across all pages in the dataset (Figure 2 and Table 1).

Figure 2: Mean brand content scores (i.e. overall online prominence scores) for the top twenty fashion brands (using the set of 545 webpages from the proof-of-concept study)

| Position |

Brand |

Mean brand content score |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nike | 0.47 |

| 2 | Gucci | 0.40 |

| 3 | Skims | 0.24 |

| 4 | Dior | 0.23 |

| 5 | Burberry | 0.23 |

| 6 | Balenciaga | 0.19 |

| 7 | Versace | 0.19 |

| 8 | Prada | 0.18 |

| 9 | Louis Vuitton | 0.17 |

| 10 | Saint Laurent | 0.15 |

| 11 | Loewe | 0.14 |

| 12 | Fendi | 0.13 |

| 13 | Valentino | 0.11 |

| 14 | Dolce & Gabbana | 0.11 |

| 15 | Moncler | 0.09 |

| 16 | JW Anderson | 0.08 |

| 17 | Diesel | 0.07 |

| 18 | Bottega Veneta | 0.04 |

| 19 | Miu Miu | 0.03 |

| 20 | Jacquemus | 0.02 |

Table 1: Mean brand content scores (i.e. overall online prominence scores) for the top twenty fashion brands (using the set of 545 webpages from the proof-of-concept study)

The analysis gives the top five brands as Nike, Gucci, Skims (the only brand in the set for which a page from the official website was returned in the first page of Google results in response to at least one of the generic, fashion-related queries), Dior, and Burberry.

The data can be alternatively visualised in terms of the distribution of brand content scores across the dataset of webpages, for each brand (Figures 3 and 4).

Figures 3 and 4: Distribution of brand content scores for the top five (top) and bottom five (bottom) brands, by mean brand content score

As would be expected, the brands with the greatest prominence appear in general on more of the pages within the dataset, and have greater numbers of pages giving higher brand page content scores.

It is also informative to compare the overall mean brand page content scores (i.e. overall online prominence scores) against the positions of the brands in the original Lyst Index ranking (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Comparison of mean brand content score against Lyst Index ranking for the top twenty fashion brands

In general, there is no strong correlation between overall prominence and brand ranking (Lyst Index), with many of the higher-ranked brands having relatively low levels of prominence in the dataset. It is noteworthy that only one (Gucci) of the top six most prominent brands appears in the top ten of the Lyst ranking. The reason for this discrepancy is presumably because the two methods are using rather distinct methodologies, aiming to measure different brand characteristics; the Lyst Index aims to provide a more general measure of brand popularity, including the frequency of use of brand-specific searches by Internet users, and mentions and engagement in content on other platforms such as social media[7]. Conversely, the approach used in our analysis is more purely measuring brand prominence and visibility, making it more closely correlated with factors connected with search-engine optimisation.

Conclusions and discussion

The methodology described in this article represents a simple approach for comparing the online prominence of different brands, focusing on the most highly-visible online content (i.e. the webpages appearing near the top of the search-engine rankings).

The same approach can also be applied to more comprehensive studies, which could incorporate larger datasets of webpages, potentially drawn from a wider range of search sources targeting different geographical markets, and utilising as many relevant search queries as appropriate. In any study of this type, it is important to deal correctly with brand names which are relatively generic, to ensure that references are considered properly and avoid false positives. For example, a reference to 'Diesel' in a set of webpages pertaining to fashion is likely to pertain to the clothing brand; however, this may not be the case in a set of pages pertaining to business more generally. In such cases, it may be necessary to make use of keyword-based filtering to distinguish the relevant mentions from other uses of the brand name.

Furthermore, providing a consistent approach is used for any given series of studies, the methodology offers the potential for tracking trends and changes over time in relative prominence (without the need to 'normalise' the scores to a consistent baseline, as was the case in some earlier studies)[8,9,10], allowing factors such as the impact of marketing initiatives or news stories to be tracked.

It would also be possible to extend the brand content scoring approach to measure other characteristics of webpage content - for example, using the proximity and strength of sentiment-related keywords to the brand mentions in order to measure brand-related sentiment.

Appendix A: The top twenty fashion brands

The table below shows the top twenty fashion brands in 2023, according to the Lyst Index, together with the text (regular expression, or Regex) strings used in our analysis to identify a 'mention' of the brand.

Notes:

.? denotes any one optional character

.* denotes any number of optional characters

| No. |

Brand |

Detection string |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Prada | prada |

| 2 | Miu Miu | miu.?miu |

| 3 | Moncler | moncler |

| 4 | Valentino | valentino |

| 5 | Loewe | loewe |

| 6 | Bottega Veneta | bottega.*veneta |

| 7 | Dolce & Gabbana | gabbana|d&g |

| 8 | Versace | versace |

| 9 | Gucci | gucci |

| 10 | Saint Laurent | yves.*laurent|ysl |

| 11 | Dior | dior |

| 12 | Nike | nike |

| 13 | Louis Vuitton | vuitton |

| 14 | Diesel | diesel |

| 15 | Burberry | burberry |

| 16 | Fendi | fendi |

| 17 | Skims | skims |

| 18 | Balenciaga | balenciaga |

| 19 | Jacquemus | jacquemus |

| 20 | JW Anderson | jw.?anderson|jonathan.?anderson |

References

[1] https://www.businessweekly.co.uk/news/hi-tech/9121-onlineresearch-gives-insight-damage-banks-brands

[2] https://www.trademarksandbrandsonline.com/news/luxurybrands-not-doing-enough-to-protect-themselves-online-4482 (cache available at https://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:9oyTNc1E1AwJ:https://www.trademarksandbrandsonline.com/news/luxury-brands-not-doing-enough-to-protect-themselvesonline-4482&sca_esv=580550388)

[3] 'The Digital Brand Risk Index: A NetNames Report'; PDF available at https://silo.tips/download/the-digital-brand-riskindex-a-netnames-report

[4] 'Technical aspects of brand monitoring', internal Stobbs training presentation

[6] https://skims.com/collections/clothing

[7] https://www.lyst.com/data/the-lyst-index/q323/

[8] https://www.tyrepress.com/2011/09/michelin-still-toponline-brand-but-the-gaps-narrowing/

[9] https://www.tyrepress.com/2016/10/michelin-returns-to-thetop-of-online-brand-ranking/

[10] https://www.tyrepress.com/2017/09/michelin-tops-onlinebrand-prominence-table/

This paper was first published as an e-book on 28 November 2023 at:

https://www.iamstobbs.com/measuring-brand-prominence-of-fashion-brands-ebook

.jpg)