BLOG POST

A recent report by consumer watchdog 'Which?'[1] highlighted the likely scale of the problem of fraudulent and copycat websites targeting brands in the banking industry. Off the back of this report, we carried out a landscape analysis considering gTLD (i.e. generic extensions such as .com, etc.) domains with names beginning with any of the eight major UK banking brands referenced in the Bank of England’s Resolvability Assessment Framework[2]. This approach (ignoring domains where brand names appear elsewhere in the domain name, unbranded domain names, and other domain-name extensions) will therefore give an extremely conservative view of the full scale of the problem.

Even just using this very simple approach, significant numbers of live, potentially fraudulent sites and other infringements targeting the banking brands were identified. The findings encompassed a range of 'tiers' of threat severity, from explicit impersonation and phishing, through the promotion of probable non-legitimate financial schemes, to other potentially unauthorised use of branding (complaints sites, informational content, misdirection of web traffic to third-party content, etc.). Even amongst the large number of additional currently-inactive domains, there is a high potential for fraudulent use and/or subsequent 'weaponisation' in scam campaigns. Of additional concern is the fact that some of the high- or intermediate-threat sites have been registered for significant periods of time (up to four years in some cases).

When the analysis is extended to cover 'fuzzy' matches to the brand names (i.e. typos and associated variants), a large number of additional examples of concern were again identified, highlighting the extent of this approach (i.e. the use of confusingly similar deceptive brand variants) by fraudsters, and the importance of using a brand-monitoring tool able to capture these examples.

In light of these findings, it would seem that there is a need for increased regulation and legislation in the domain-name-sales industry, since in many cases there is no legitimate reason why a non-brand-owner should be registering large numbers of domains featuring variants of a trusted and rights-protected brand name.

References

This article was first published on 29 April 2024 at:

* * * * *

WHITE PAPER

A March 2023 report by consumer watchdog 'Which?', in partnership with the DNS Research Foundation, highlighted the extent of the problem of financial fraud and copycat banking websites. Their analysis revealed that more than 2,000 suspected lookalike websites targeting the top UK banking brands were identified in 2023, based on analysis of phishing and fraud blocklists for cases where any of the brand names appear in the URLs of the infringing sites[1,2]. The data is likely to be (potentially significantly) a lower limit for the true number of cases, bearing in mind the focus on branded URLs, the inability to incorporate meaningful analysis of the more generic brand names, and the fact that only sites which are identifiable and sufficiently long-lived to have been included on the blocklists were considered.

As a deeper dive, we consider the landscape of registered domains[3] with names containing any of the eight major UK banking brands[4] as referenced in the Bank of England's Resolvability Assessment Framework[5]. In order to focus on the highest-relevance domains, we consider only domains where the brand name appears at the start of the domain name, and analyse only gTLDs (generic extensions, such as .com, etc.) (for which comprehensive zone-file data is available). Even just this part of the methodology (focusing solely on gTLD domains containing the brand name at the start) will mean that the analysis will very conservatively reflect the overall scale of the infringement landscape.

We firstly exclude any domains which appear to be under the ownership of the official brand owner in question, on the basis of registrant or registrar identifiers explicitly given in the domain registration ('whois') records (where available via an automated look-up). In general, brand owners will maintain a portfolio of both 'core' domains (used in the general day-to-day execution of their business) and 'tactical' domains (comprising defensive and strategic - e.g. intended for future use - registrations).

Following the removal of official domains, a dataset of almost 14,000 (probable) third-party domains was obtained, for the eight banking brands. In order to further focus on those sites most likely to be relevant to the brands in question (and disregard generic, unrelated or third-party uses of the brand names, which include examples such as Lloyds (also a surname), Nationwide (a generic term), and Santander (also a location)), we focus only on those domains featuring banking- or finance-related or other significant keywords in the domain name or in the site content. This filtering yields a set of around 3,200 domains.

The next stage of analysis involves considering only those domains resolving to live website content (i.e. returning an HTTP status code of 200), of which there were just over 2,400. However, the remainder may still be of potential concern, perhaps comprising instances of cybersquatting, or domains intended for activation ('weaponisation') at a later date.

40 of the approximately 2,400 sites were found to resolve or re-direct to what appear to be official websites for the banking brands in question (despite not being registered with official corporate contact details). In some of these cases, the authenticity of the sites was unclear, by virtue of factors such as domain registration via a retail-grade registrar (with examples such as Tucows and GoDaddy appearing in the dataset), highlighting that there may be cases where the brands have not consolidated their official registrations through enterprise-class providers.

Even in cases where the a site was found to re-direct to a domain which is definitively official (e.g. hsbc.com, lloydsbank.com, natwest.com, santander.com, barclays.co.uk, etc.), this does not necessarily mean that the referring site is innocuous. For example, it is a well-established phishing technique to register a deceptive name to be used as the 'from' address in an email campaign, but configure the domain to re-direct to a legitimate official site, so as to provide an appearance of authenticity.

Of the remaining sites, we then focus on the subset presenting the highest potential threat; namely, those featuring highly relevant keywords such as 'bank' or 'login' in their page title. This yielded a high-priority dataset of just over 100 domain names for more detailed analysis.

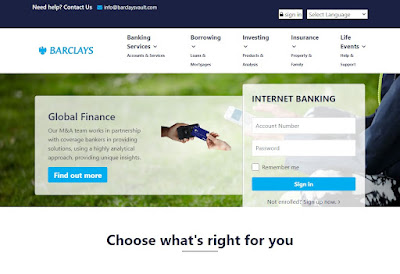

Concerningly, purely this simple approach allowed us to identify a number of instances of live, potentially fraudulent sites and other infringements targeting the banking brands. The highest-threat tier of findings are those sites which explicitly appear to be impersonating the brand in question (with varying degrees of quality), presumably as part of phishing attempts or other forms of financial fraud campaign (14 examples in the high-priority dataset) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Examples of high-threat sites apparently impersonating banking brands (SLDs (second-level domain names, i.e. the part of the domain name to the left of the dot): barclaysbk, barclaysvault, lloydsibankgroup, lloydswealthassetmanagement, natwestbankonline, natwestbonds, natwestsantander, hsbcglobalbank)

The next highest (i.e. intermediate threat) level of findings are those sites which appear to be using the brand name in conjunction with finance-related content appearing likely to be non-legitimate, but which seem not to be explicitly impersonating the banking brand in question (12 examples in the high-priority dataset) (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Examples of intermediate-threat sites utilising a banking brand name in conjunction with probable non-legitimate finance-related content (SLDs: lloydsgroups, hsbcapitalfx)

Included amongst the lower-threat findings are some examples of sites making potentially unauthorised use of branding in other contexts (some of which may not be enforceable), such as complaints sites, informational content, websites promoting their own products or services, or other sites which may be official but are not registered with centralised contact details (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Examples of lower-threat sites making potential unauthorised use of official branding (SLDs: lloydsbankassetfrauds, natwestcon, hsbc-otasuke, santandergpt)

A range of content types was identified within the remainder of the dataset, including instances of third-party content, adult sites, pages offering the domain names for sale, and other placeholder content. Some of these page styles have previously been identified as content types which are typically displayed as 'dummy' content, used to mask more serious infringements which may have their access 'geoblocked', or which are only active at particular times or on particular days[6].

Amongst the set of 26 'high' and 'intermediate' threat site, it is noteworthy that the registrations are dominated by the use of retail-grade registrars and explicit use of privacy-protection services. The sites encompass a wide range of ages (registered between 08- Jul-2020 (1,365 days old at the time of analysis) and 01-Apr-2024 (2 days old)). The presence of examples at both ends of this spectrum is concerning, because of the longevity of some of the sites and the fact that registration of (new) infringements is ongoing.

We next extend the analysis to consider domains where a fuzzy match to any of the brand names (i.e. instances of (single) replaced, missing, additional or transposed characters) appears at the start of the domain name. These types of typo variants have extensively been noted as being popular with infringers in the creation of deceptive and fraudulent sites[7,8].

From these broad searches, a set of over 57,000 domain names was returned. From these, we again remove any which are explicitly under the official ownership of the brand in question (634 domains), together with a number of others which are most likely to be non-relevant.

These include:

- all domains featuring a missing- or replacedcharacter variant of 'hsbc' (since these types of variants - such as ‘absc’, ‘sbc’, etc. - are likely to be unrelated to the brand, given the short length of the character string)

- (replaced-character) domains beginning with just 'barclay', 'lloyd' or 'floyd', unless they also feature banking or finance-related keywords, or other features suggesting they may be of concern (e.g. domains where the brand variant comprises the entirety of the SLD name, or where the domains are classified as additional-character variants - e.g. strings such as 'lloydXs', where 'X' is some other character)

This yields a dataset of 3,231 domains of potential relevance. Of these, we then focus only on those resolving to live websites and also featuring relevant keywords either in the domain name or on the page. This gives a candidate set of exactly 500 domains for further analysis.

Of these 500, 21 were found to resolve to high- or intermediate-threat sites, according to the definitions used previously (Figure 4). Further examples may also previously have been live, but subsequently been taken down.

Figure 4: High- or intermediate-threat sites hosted on domain names utilising fuzzy variants of the name of the brand being targeted (SLDs: barlaysb, braclaysonline, barrclaysfedunion, barc-laysfin, hssbcc, hsbkcapital, hsbkc-corporation, hesbc, llyodsgroup, nationswidefund, natlwestmb, netwestfin, natiwest, netwestoffshore, nalwest, santender, satanderonline, satandercredit, satandertrades, santandenow, standardchateredsplc)

We also see instances of shared templates being used for different sites (e.g. the braclaysonline and satandercredit examples shown above), suggesting links between the infringers and/or the use of common phishing-site 'kits'.

Amongst the remainder, there are large numbers of domains resolving to third-party sites (in many cases, comprising potentially legitimate uses of the brand variants in question). A significant proportion also resolve to pay-per-click (PPC) pages, suggesting in these cases that the domain names may have been registered speculatively in an attempt to attract misdirected traffic from mistyped URLs or search queries intended for the banking brands in question, and are monetising the visitors to these sites through the generation of click-through revenue.

Additionally, the closeness of the match to the brand name in question of many of the (currently inactive) domains outside this group of 500 is highly suggestive that they may also be likely to have been registered for future fraudulent use. The numbers of concerning findings identified through these simple searches provides an additional illustration of the likely scale of the fraud problem targeting financial brands. This is particularly true given that we have only considered gTLD domains where the brand name (or variant) appears at the start, and does not even consider infringing sites hosted on non-brand specific and/or other compromised domain names. The findings highlight the importance of brand owners employing comprehensive programmes of brand protection and domain-name management, which are able to address brand variants as well as exact matches, over as wide a range of domain extensions as possible, and also incorporating coverage of general Internet content and phishing data from other sources. Such programmes need to encompass monitoring, prioritisation and analysis of findings, and rapid enforcement against damaging content.

This view of the landscape also raises wider questions about the state of the domain industry and the potential need for more stringent regulation and legislation. The initial article by Which? suggests a push to force domain registrars to do more to prevent these scams appearing in the first place. It might be appropriate to set the bar for 'infringement' at rather a lower level than currently; the suggestion has been made that there is no legitimate reason why a non-brand owner should be registering large numbers of domains featuring variants of a trusted and rights-protected brand name[9,10] - this type of activity potentially could and should be stopped by registrars at the point of attempted registration.

References

[3] Based on analysis carried out on 03-Apr-2024

[4] The monitored strings are: barclays, hsbc, lloyds, nationwide, natwest, santander, standard(-)chartered, and virgin(-)money. '(-)' denotes an optional hyphen.

[6] https://circleid.com/posts/20220531-do-you-see-what-i-see-geotargeting-in-brand-infringements

[7] https://www.cscdbs.com/en/resources-news/threatening-domains-targeting-top-brands/

[8] https://www.iamstobbs.com/idns-ebook

[10] J. Williams, XConnect (pers. comm., 02-Apr-2024)

This article was first published as an e-book on 29 April 2024 at: