BLOG POST

The launch of Google's new artificial intelligence model 'Gemini' on 6 December was one of the most significant recent brand launches, and was followed almost immediately by a spike in associated brand infringements. The findings highlight the importance of a proactive programme of brand monitoring, as part of a wider brand protection (BP) initiative, but monitoring can be difficult in instances where - as in this case - the brand name is a generic term which is frequently used in unrelated contexts (specifically astrology in this instance).

In our latest study, we show how the application of 'positive' (relevance) and 'negative' (exclusion, or non-relevance) keywords used together can achieve an effective separation between relevant and non-relevant results, particularly when also combined with the utilisation of focused search keywords in the brand monitoring configuration.

These ideas are key to the implementation of an efficient BP programme, to avoid expensive spends on time required to manually review and filter out false positives - and also minimise the chances of significant findings being overlooked. It is also worth noting, however, that part of a holistic BP initiative should involve the review of 'borderline' results (which are neither obviously explicitly relevant nor non-relevant), to identify significant third-party brand uses - accordingly, it is essential to bear this point in mind when selecting the search terms to be used and the thresholds to be set for the relevance cut-offs.

This article was first published on 12 January 2024 at:

* * * * *

WHITE PAPER

Introduction

The launch of Google DeepMind's new artificial intelligence (AI) model 'Gemini'[1] on 6-Dec-2023 was one of the latest in a line of high-profile (even if somewhat controversial[2,3]) brand launches, and potentially the most significant in the AI arena since ChatGPT[4,5,6]. Within a week of its launch, Gemini was predictably already subject to large numbers of potential brand infringements, including significant numbers of domain registrations utilising the brand name as a means of passing themselves off as official or affiliated sites, misdirecting users to their own content, monetising search-based web traffic, or offering the domain names for sale (Figure 1). In total, 383 domains containing 'gemini' (including 43 containing 'ai', and 16, 22 and 16 containing 'ultra', 'pro' and 'nano' (the three variant Gemini models offered by Google), respectively) were registered in the two days between 6th and 7th December, compared with an average of 7.97 registrations per day across 2023 prior to 6th December[7].

Figure 1: Examples of apparently unofficial live websites hosted on Gemini-specific domain names within a week of brand launch

The generic nature of the Gemini brand name (which is commonly used in the context of astrology) means it presents a number of complications from a brand-protection point of view. Aside from the potential difficulties in securing relevant intellectual property protection and conducting enforcement actions against infringements, it is not even straightforward to monitor for relevant online content which may be of brand relevance or infringing, and to separate out false positives (i.e. mentions which are unrelated to the brand) - although this is clearly of importance when a high-profile brand is launched.

In this study, we consider the use of appropriate search strategies and keyword-based filtering which can be utilised to construct an effective and efficient Internet monitoring programme. The study builds on the concept of brand content scoring (together with ideas relating to search strategies and keyword matching), discussed in previous Stobbs studies of online prominence and sentiment[8,9] as a means of quantifying the amount and prominence of brand- or keyword-related content on a webpage.

Analysis

In the initial part of the study, we consider simply the first page of search results (94 URLs) returned by google.com in response to the search term 'gemini'[10]. As might be expected, this returns a mixture of content, including material relating to the Google Gemini brand, content relating to the term in an astrological content, and other webpages, including third-party usage of the same brand name in a way which may or may not be infringing.

In general, it is often desirable to be able to separate out these categories of content. This is necessary not only in general brand monitoring, where it is primarily only brand-related or potentially infringing content which is of interest, but also in (for example) studies of comparative online prominence, which are generally most meaningful if 'false positive' references can be excluded.

The simplest way to carry out the filtering is via the use of 'positive filtering' (relevance) or 'negative filtering' (exclusion) keywords. (Note that, in this context, we are not using the terms 'positive' and 'negative' to denote sentiment!) In this study, we consider the page to be likely to be relevant to the Gemini brand if it also contains any of the following (company- or industry-specific) ('positive') keywords:

- DeepMind

- AI*

- A.I.*

- LLM* (Large Language Model)

- MMLU* (Massive Multitask Language Understanding)

- GPT*

- ChatGPT

*terms marked with an asterisk must appear in isolation, or prefixed or suffixed by characters other than letters - e.g. we do not want to consider words where (for example) 'ai' appears as a sub-string (such as 'traits')

Similarly, we can construct a list of 'negative' keywords, which are likely to be present only if the Gemini name is mentioned in an explicitly non-relevant context (i.e. astrology):

- Capricorn

- Aquarius

- Pisces

- Taurus

- Scorpio

- Sagittarius

- 'astrolog' (covers wildcard variants such as 'astrology' and 'astrologer')

- zodiac

- Castor

- Pollux (Castor and Pollux are the 'twin' stars in the Gemini constellation)

It is advisable to select these keywords carefully to avoid including any terms which are more generic (and can appear in unrelated contexts) or which can appear as sub-strings of longer words (if wildcard matching is used)[11].

Rather than then simply treating pages as either relevant or non-relevant based on the appearance of any mention of a corresponding keyword, we adopt the approach of calculating the webpage content score for each of the above keywords. The sum of the scores of the 'positive' keywords thereby provides a measure of the likelihood of the page being relevant, and vice versa. A useful measure of overall potential relevance is then the difference between the total 'positive' (relevance) score and the total 'negative' (non-relevance) scores.

There are a couple of specific points to note with this approach:

- We would not want to include or exclude a page purely on the basis of any mention of a keyword, as these terms can sometimes appear in their 'opposite' context. For example, we may find some pages primarily relating to Google Gemini but which also feature a minor reference(s) to astrology[12] (such as may occur if a page makes reference to the fact that Gemini is named after the astrological star sign). Conversely, a relevance keyword may appear on an otherwise non-relevant site (particularly with a term such as 'Google' which can appear in links, advertisements, tracking functionality, etc. on websites).

- We do not necessarily want to set the 'threshold' at which we consider a page to be relevant / non-relevant at a net score of zero. As described above, some relevant pages may feature 'negative' keywords and, overall, some of the most significant pages (particularly when considering third-party uses of the same brand name) may yield scores of around zero, particularly when pertaining to less directly relevant business areas[13]. Accordingly, when collecting a set of pages for consideration from a brand analysis point of view, it is likely to be advisable to retain all pages down to a (small) negative score. Additionally, the zero-point is somewhat arbitrary, particularly if the analysis is utilising differing numbers of 'positive' and 'negative' keywords.

Overall, this technique does provide a good means of filtering by relevance; the top five (i.e. most likely to relate to Google Gemini) and bottom five (i.e. most likely to relate to astrology) pages, as ranked by overall potential relevance score, are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

| Page title |

Webpage host domain |

Potential relevance score |

|---|---|---|

| Google launches Gemini, the AI model it hopes will take ... | theverge.com | 444 |

| Google Gemini Vs OpenAI ChatGPT: What's Better? | businessinsider.com | 359 |

| Google I/O 2023: Making AI more helpful for everyone | blog.google | 358 |

| Google says new AI model Gemini outperforms ChatGPT in ... | theguardian.com | 322 |

| Google's New AI, Gemini, Beats ChatGPT In 30 Of 32 Test ... | forbes.com | 319 |

Table 1: Top five pages by potential relevance score

| Page title | Webpage host domain | Potential relevance score |

|---|---|---|

| Gemini Zodiac Sign: Characteristics, Dates, & More | astrology.com | -248 |

| Gemini Zodiac Sign: Horoscope, Dates & Personality Traits | zodiacsign.com | -232 |

| The Gemini - Zodiac Sign Dates and Personality | thoughtcatalog.com | -200 |

| Gemini Personality Traits - The Times of India | indiatimes.com | -186 |

| All About Gemini | tarot.com | -174 |

Table 2: Bottom five pages by potential relevance score

By manual inspection, we find that - in general - all pages with a potential relevance score below approximately -20 (negative 20) in this particular dataset are non-relevant (i.e. primarily about astrology); the remainder would be potential candidates for further analysis from a brand-monitoring point of view (i.e. are potentially relevant) - this equates to 73 of the 94 results returned by the search query (i.e. 78%).

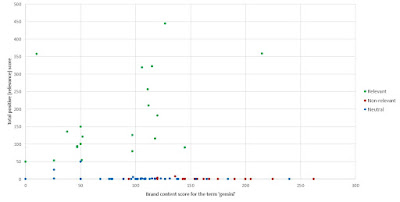

An alternative way of visualising this categorisation is to manually classify each of the 94 pages as definitively relevant (i.e. relating to Google Gemini), definitively non-relevant (i.e. relating to a false positive (astrology)), or 'neutral' (i.e. potential third party / other references to the Gemini name), and plot the set of pages according to their potential relevance score. This relationship is shown in Figure 2, highlighting that the categorisation by the use of potential relevance score is relatively 'clean' (i.e. the relevant pages generally appear at the top (with high potential relevance scores) and the non-relevant pages at the bottom).

Figure 2: Relationship between potential relevance score and manual categorisation of actual relevance, for each of the pages in the dataset

(N.B. the horizontal axis shows the brand content score for the term 'gemini' in each case which, in itself, is not a helpful basis for categorisation, since the term can appear in either relevant or non-relevant contexts)

It is important to note that this approach (i.e. considering the balance between the 'positive' and 'negative' keywords) can be seen to provide a better ('cleaner') separation of relevant from non-relevant results than just using either set of keywords in isolation (i.e. applying only a 'positive filtering' or only a 'negative filtering' approach, for the reasons discussed in point (1.) above). This comparison is shown in Figures 3 and 4.

Figure 3: Relationship between total 'positive' (relevance) score only and manual categorisation of actual relevance, for each of the pages in the dataset

Figure 4: Relationship between total 'negative' (non-relevance) score only and manual categorisation of actual relevance, for each of the pages in the dataset

Furthermore, it is possible to take this approach (i.e. the application of techniques to filter down a set of 'raw' results to the subset most likely to be relevant) one step further, through the explicit use of relevant (focused) search terms (i.e. the 'positive' keywords). In order to demonstrate this, we construct a series of searches in which the Gemini name is combined in turn with each of the 'positive' keywords, and then again extract the first page of results returned by google.com in each case - i.e. we search for:

- gemini deepmind

- gemini google

- gemini ai

etc.

Once the results are de-duplicated (since the same URL may, in general, be returned by more than one of the above search terms), this yields a dataset of 486 distinct URLs.

In this case. The 'hit-rate' of relevant results is (unsurprisingly) much higher - none of these URLs yields a potential relevance score below zero, and - by manual inspection - all appear potentially relevant, with none of the results appearing to relate primarily to astrology (Figure 5). However, what this dataset does not potentially encompass is instances of usage of the Gemini name by third parties in industries outside AI; if this type of content is of interest, this consideration must be borne in mind when selecting the search queries for a programme of brand monitoring.

Figure 5: Comparison of the spread of potential relevance scores across the sets of pages returned by an unfocused search query (brand name only) and by focused queries (brand name plus relevance keywords)

It is also worth noting that this type of relevance filtering is also a consideration when measuring the online prominence of brands. If, for example, we just calculate the average brand content score for the term 'Gemini' across the sets of pages returned in each case, we obtain values of 107 for the unfocused dataset and 81 (i.e. actually a lower value) for the focused dataset, on which far more of the pages are actually relevant and relate to the brand in question. Of course, the difference is that many of the references to 'Gemini' in the former dataset will be unrelated to the brand in question (in many cases, referring to astrology), but this would not necessarily be apparent if purely the raw numbers were considered (see also Figure 2).

Key take-aways

In a brand-monitoring context, the use of both 'positive filtering' (relevance) and 'negative filtering' (exclusion) keywords together, combined with ideas related to the concept of content scoring (a means of quantifying the amount and prominence of mentions of a particular term on a page - or the extent to which a page is 'about' that term), but applied to these keywords, rather than to a brand name, provides an effective means of categorising relevant from non-relevant pages, in cases where the brand name itself is a generic term.

When combined with the application of relevance keywords in the search queries used to generate results, this approach is an efficient way of collecting a sample of pages relevant to a particular brand, and minimises the amount of analysis time required to filter out false positives. However, in many brand-monitoring contexts, pages which are essentially 'neutral' in character (e.g. relating to third-party use of the same brand name in potentially separate business areas) can be of interest, and it is therefore necessary to carefully select the search terms and scoring thresholds used, so as to avoid missing potentially significant findings.

Overall, however, the ideas presented in this study are key to the configuration of an efficient brand-monitoring solution which can effectively exclude false positives. Without these approaches, the sets of results identified through automated technologies can be dominated by non-relevant findings, which not only increases the cost of a service from the point of view of the amount of resource required to review the results, but can also lead to an increased possibility of relevant findings being overlooked. When combined with a content-scoring approach to prioritise the remaining (relevant) findings (in order to identify priority targets for more in-depth analysis, content tracking, or enforcement), a highly efficient brand-protection programme can be implemented.

References

[1] https://deepmind.google/technologies/gemini/ - Interestingly, a good example of a 'dot-brand' domain for an official website

[2] https://www.theverge.com/2023/12/7/23992737/google-gemini-misrepresentation-ai-accusation

[5] https://www.zdnet.com/article/what-is-google-gemini/

[7] Considering only gTLD registrations as present in zone-files available via ICANN's CZDS service as of 13-Dec-2023, and where whois information is available via an automated look-up

[8] https://www.iamstobbs.com/measuring-brand-prominence-of-fashion-brands-ebook

[9] https://www.iamstobbs.com/online-brand-prominence-and-sentiment-ebook

[10] Results are based on searches and analysis carried out on 13-Dec-2023

[11] For example, in an early test, the word 'aries' (subsequently excluded from the list) was identified on a webpage (https://www.ft.com/content/e5cc4e36-efe3-4491-b435-75a712533257) featuring an article about Google Gemini, within a link on the page to the 'obituaries' section of the website

[12] e.g. https://www.news9live.com/technology/googles-deepmind-debuts-gemini-ai-model-to-compete-with-openais-gpt-4-2370930, which also features a link to the 'astrology' section of their website

[13] A good example is https://www.gemini.com/ (actually the top ranked result in the page of Google results), which yields an overall potential relevance score of 1. The site offers a cryptocurrency trading service, and it is unclear even on initial manual inspection whether it is passing off as being related to the Google Gemini brand, or whether it is using the same name as an unrelated third party. Even if so, further analysis would be needed to determine whether it is infringing Google IP, based on factors such as the trademark classes in which protection is held, geographical presence, and pre-existence.

This article was first published as an e-book on 12 January 2024 at:

No comments:

Post a Comment